A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

See the complete list of topics.

Gastrointestinal Issues and Oral Motor Behaviors | Genetic Counseling | Genetics 101 | Genotype to Phenotype Relationship | GERD |Germ Cell Mosaicism | Gifts| Government Assistance| Guardianship

Gastrointestinal Issues and Oral Motor Behaviors

The following is an expert from Facts About Angelman Syndrome.

Feeding problems are frequent but not generally severe and usually manifest early as difficulty in sucking or swallowing [67-‐69]. Tongue movements may be uncoordinated with thrusting and generalized oral-motor incoordination. There may be trouble initiating sucking and sustaining breast feeding, and bottle feeding may prove easier. Frequent spitting up may be interpreted as formula intolerance or gastroesophageal reflux. The feeding difficulties often first present to the physician as a problem of poor weight gain or as a “ʺfailure to thrive”ʺ concern. Infrequently, severe gastroesophageal reflux may require surgery.

Angelman children are notorious for putting everything in their mouths. In early infancy, hand sucking (and sometimes foot sucking) is frequent. Later, most exploratory play is by oral manipulation and chewing. The tongue appears to be of normal shape and size, but in 30-50%, persistent tongue protrusion is a distinctive feature. Some have constant protrusion and drooling while others have protrusion that is noticeable only during laughter. Some infants with protrusion eventually have no noticeable problem during later childhood (some seem to improve after oral-motor therapy). For the usual AS child with protruding tongue behavior, the problem remains throughout childhood and can persist into adulthood. Drooling is frequently a persistent problem, often requiring bibs. Use of temporary medications such as scopolamine to dry secretions usually does not provide an adequate long term effect. Surgical procedures to ameliorate drooling are possible [70] but apparently rarely used in AS.

The following expert is from the National Organization for Rare Disease (NORD) webpage about AS.

Feeding difficulties may be treated by modified breast feeding methods and by means such as special nipples to assist infants with a poor ability to suck. Gastroesophageal reflux may be treated by upright positioning and drugs that aid the movement of food through the digestive system (motility drugs). Surgical tightening of the valve that connects the esophagus to the stomach (esophageal sphincter) may be required in some cases. Laxatives may be used to treat constipation.

Genetic Counseling

Angelman Family Contribution

When your child is diagnosed with AS, and if the child has the UBE3A mutation, make sure the mother is tested to see if she is a carrier. (That is if you want to have more children.) That way you will know if there is a chance your next child could have AS.

AS Family Member

A genetic counselor can inform you on the possibility for Angelman syndrome to occur or recur through gathering family history and blood testing.

Do not use the following aspects in lieu of consulting with a genetic counselor. These are aspects to consider in understanding AS genetic risk:

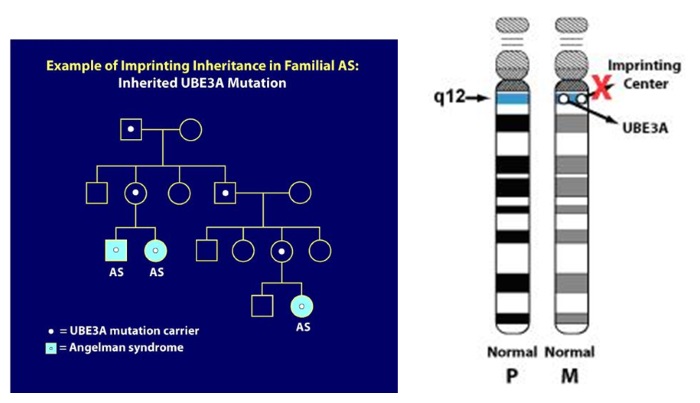

1. Common chromosome deletion:

More that 98% of the chromosome deletion instances occur by a spontaneous event and thus they are not inherited; the recurrence risk is <<1% for these families. However, 1-2% of deletions occur because of an inherited abnormality in the maternal chromosome 15, such as a balanced chromosome translocation. Another very small group (e.g., only a few cases reported in the literature), can have AS due to a very small, maternally inherited chromosome deletion that involves a small area around and including the UBE3A gene. For these cases, the maternal recurrence risk is increased depending on the type of abnormality present. Chromosome study of the mother, including FISH, helps rule out inherited chromosome 15 abnormalities.

2. Paternal uniparental disomy (UPD):

More than 99% of patUPD cases occur as an apparent spontaneous, non-inherited, event. If an individual has AS due to patUPD and has a normal karyotype, a chromosomal analysis of the mother should nevertheless be offered in order to exclude the rare possibility that a Robertsonian translocation or marker chromosome was a predisposing factor (e.g., via generation of maternal gamete that was nullisomic for chromosome 15, with subsequent post-zygotic “correction” to paternal disomy).

3. Imprinting Center (IC) Defect:

There are two types of IC defects: deletions and non-deletions. Non-deletion events do not appear to be inherited and have a <1% recurrence risk. Most deletions are not inherited but a significant proportion of them are (i.e., maternally inherited), and these confer a 50% risk for recurrence.

4. UBE3A mutations:

UBE3A mutation can either occur spontaneously (e.g., not inherited and with no increased recurrence risk) or be maternally inherited and have a 50% risk of recurrence (see below for imprinting inheritance).

5. Individuals with no known mechanism (all 4 above mechanisms have been eliminated):

For parents of AS individuals who have apparent normal genetic tests (no evidence for deletion, imprinting defect, UPD or UBE3A mutation), and thus their children are only clinically diagnosed, it is not known what the recurrence risk is. An increased risk seems likely but probably does not exceed 10%.

6. Germ cell mosaicism:

This term refers to a phenomenon in which a genetic defect is present in the cells of the gonad (ovary in the mother’s case) but not in other cells of the body. This occurrence can lead to errors in risk assessment because a genetic test, for example on a mother’s blood cells, will be normal when in fact a genetic defect is present in the germline cells of her ovary. Fortunately, germ cell mosaicism occurs very infrequently. Nevertheless, it has been observed in AS caused by the mechanisms of large chromosome deletion, Imprinting Center deletion and UBE3A mutation.

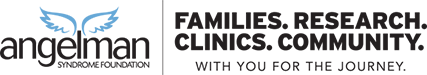

7. Imprinting inheritance:

UBE3A mutations and Imprinting Center deletions can exhibit imprinting inheritance wherein a carrier father can pass on the genetic defect to his children without it causing any problems, but whenever a female passes this same genetic defect on to her children, regardless of the sex of her child, that child will have AS. The pedigree diagram below illustrates imprinting inheritance. Here, AS has only occurred after a carrier mother passed on the gene defect (for example as in the two siblings with AS pictured on the left lower part of the pedigree). In addition, a distant cousin in this family also has AS due to the imprinting inheritance. In the diagram, individuals with the light blue circles or squares have AS but everyone else in the family is clinically normal. The white dots represent asymptomatic, normal carriers of the AS mutation. When an AS genetic mechanism is determined to be inherited, genetic testing of family members can usually identify carriers of the gene defect. As you might imagine, professional genetic counseling is advised in these situations.

Genetics 101

A report was authored by Rebecca D Burdine PhD and Erin Sheldon

Reviewed for accuracy by Wen-Hann Tan, BMBS Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston MA

Read it here.

Also, see more about the Genetics of Angelman syndrome here.

Genotype to Phenotype Relationship

Does the type of genetic cause of Angelman Syndrome make a difference in development?

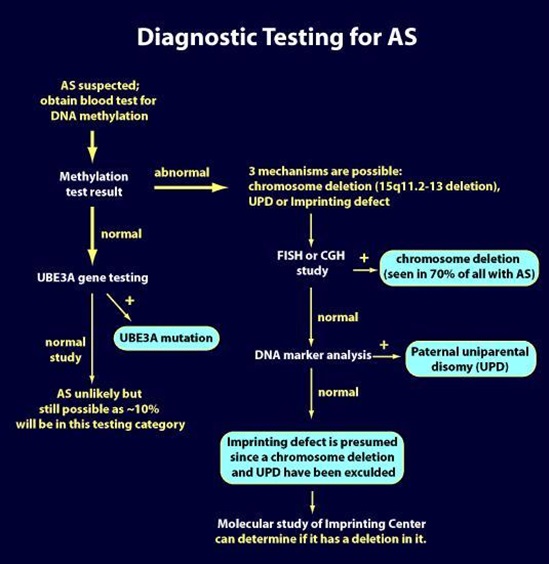

Dr. Charles Williams used the illustration below in a presentation at the 2014 CASS (Canadian Angelman Syndrome Organization) conference.

The following is taken from an article written by Aditi I Dagli, MD, Jennifer Mueller, MS, CGC, and Charles A Williams, MD. for Gene Reviews publication.

All genetic mechanisms that give rise to AS lead to a somewhat uniform clinical picture of severe-to-profound intellectual disability, movement disorder, characteristic behaviors, and severe limitations in speech and language. However, some clinical differences correlate with genotype [Fridman et al 2000, Lossie et al 2001, Varela et al 2004, Tan et al 2011, Valente et al 2013]. These correlations are broadly summarized below:

- The 5- to 7-Mb deletion class results in the most severe phenotype with microcephaly, seizures, motor difficulties (e.g., ataxia, muscular hypotonia, feeding difficulties), and language impairment. They also have lower body mass index compared to individuals with UPD or imprinting defects [Tan et al 2011]. There is some suggestion that individuals with larger deletions (e.g., BP1-BP3 [class I; ISCA-37404] break points) may have more language impairment or autistic traits than those with BP2-BP3 (class II; ISCA-37478) break points [Sahoo et al 2006] (see Figure 2).

- Individuals with UPD have better physical growth (e.g., less likelihood of microcephaly), fewer movement abnormalities, less ataxia, and a lower prevalence (but not absence) of seizures than do those with other underlying molecular mechanisms [Lossie et al 2001, Saitoh et al 2005, Valente et al 2013].

- Individuals with IDs or UPD have higher developmental and language ability than those with other underlying molecular mechanisms. Individuals who are mosaic for the nondeletion ID (approximately 20% of the ID group) have the most advanced speech abilities; they may speak up to 50-60 words and use simple sentences.

- Individuals with chromosome deletions encompassing OCA2 frequently have hypopigmented irides, skin, and hair. OCA2 encodes a protein important in tyrosine metabolism that is associated with the development of pigment in the skin, hair, and irides (see Oculocutaneous Albinism Type 2). However, other factors in addition to haploinsufficiency of OCA2 appear to account for the relative hypopigmentation in individuals with AS, as UBE3A has now been shown to modulate melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) activity in somatic tissues.

GERD

Also see A – Acid Reflux

What Is Gastroesophageal Reflux?

Gastroesophageal refers to the stomach and esophagus. Reflux means to flow back or return. Therefore, gastroesophageal reflux is the return of the stomach’s contents back up into the esophagus.

In normal digestion, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) opens to allow food to pass into the stomach and closes to prevent food and acidic stomach juices from flowing back into the esophagus. Gastroesophageal reflux occurs when the LES is weak or relaxes inappropriately, allowing the stomach’s contents to flow up into the esophagus.

Germ Cell Mosaicism

This term refers to a phenomenon in which a genetic defect is present in the cells of the gonad (ovary in the mother’s case) but not in other cells of the body. This occurrence can lead to errors in risk assessment because a genetic test, for example on a mother’s blood cells, will be normal when in fact a genetic defect is present in the germline cells of her ovary. Fortunately, germ cell mosaicism occurs very infrequently. Nevertheless, it has been observed in AS caused by the mechanisms of large chromosome deletion, Imprinting Center deletion and UBE3A mutation.

Gifts

See T-Toys

Angelman Family Contributions

Be generous with care staff. We like to give gifts to let them know they are appreciated. Even a nice hand-written card or handmade gift is wonderful. They are underpaid for the job they do.

AS Family Member

We tend to be very generous with gifts to our son’s caregivers. They work hard and are underpaid!!

AS Family Member

Our son always enjoyed soft or sturdy talking toys and stretchy items, bath toys and also blocks that can be put in and out of containers, like a mailbox shape sorter, or simply Legos and large plastic containers!

Andrea, mcneilak98@gmail.com, angel Tyler, age 18, Del+ Class 1

My tip is to make unwrapping one of the highlights of the moment. My daughter loves slowly pulling apart the paper and finding the gift inside. When everyone else is done with Christmas unwrapping, we all love to watch her take her time with a big smile as she slowly unwraps each gift.

Sarah, bnamommyisfun@yahoo.com, angel Lily, age 14, Del+

Government Assistance

Resources and Services specific to State Waivers, Government Assistance, Insurance and Advocacy.

Contact Dr. Eric Wright, ASF Family Resource Team via a form on the ASF website.

Eric’s experiences as an elementary school guidance counselor and teacher at the university level in Education and Human Development make him the ASF’s Government/Insurance/Advocacy guru. Along with helping AS families navigate through the red tape of waivers, assistance, and insurance, he also serves as consultant on the Bureau of Maternal Child Health/Pacer Program as well as on the Medicaid Technical Advisory Council and Commonwealth Council on Developmental Disabilities.

Eric and his wife Debbie have three children: Ella, Elsie (Del+), and Ethan. The Wrights love traveling, horseback riding, and swimming together. Together Eric and Debbie continue to seek out resources to best serve other AS families.

Guardianship

See the National Guardianship Association website. The map provides information about state guardianship associations across the country. Click on individual states to learn more.

Adult Guardianship: Watch the ASF Educational Webinar on Guardianship, presented by Dr. Eric Wright.